Renewing STA Serves Interests of All Parties

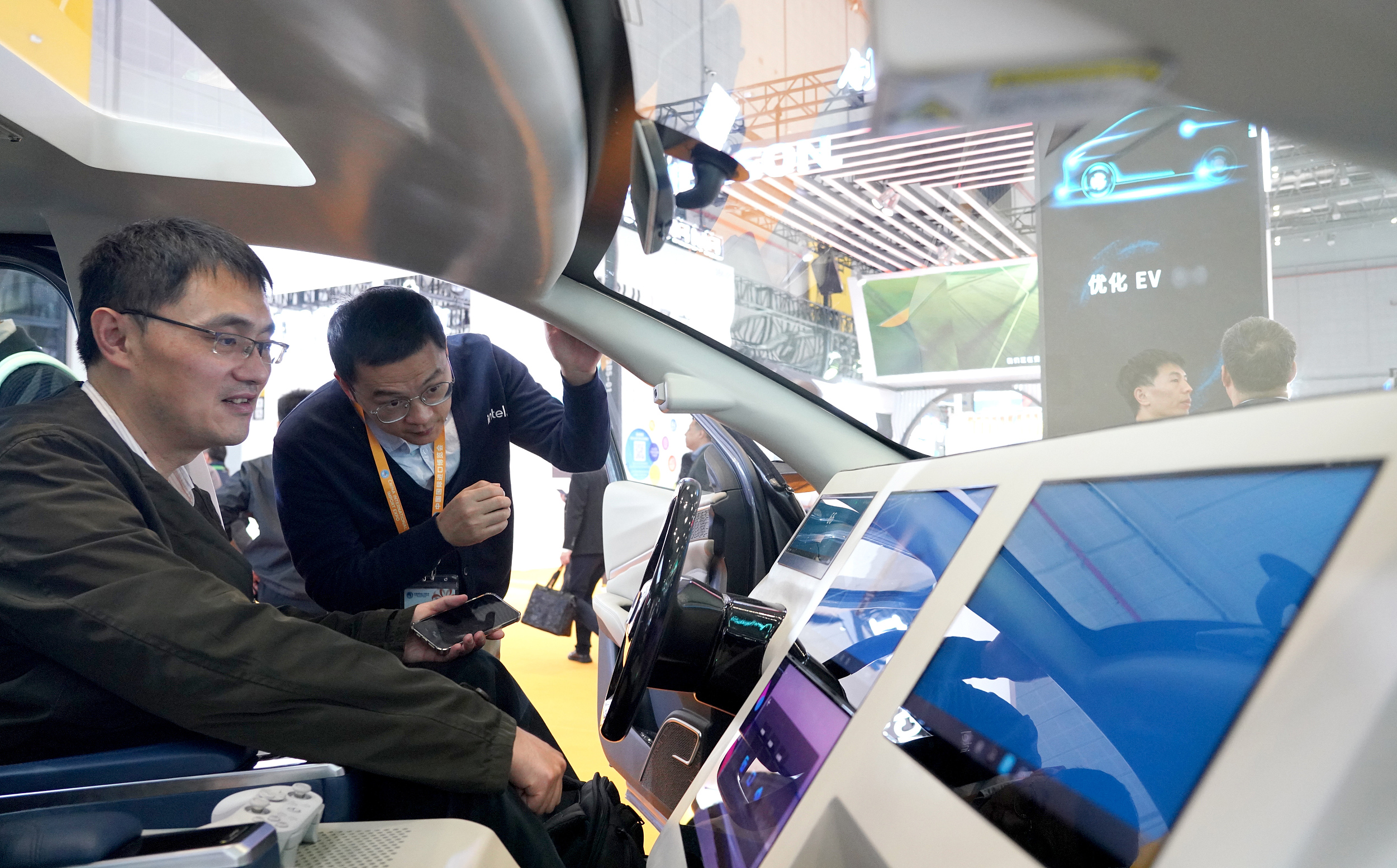

Visitors experience Intel's intelligent cockpit platform at the Intel booth of the 6th China International Import Expo on November 8, 2023.

By?QI?Liming

On December 15, Nicholas Burns, U.S. Ambassador to China, delivered a speech at the Brookings Institution, during which he mentioned that he had begun talks with China on renewing a landmark scientific cooperation agreement: U.S.-China Science and Technology Agreement (STA).

The U.S. State Department had sought a six-month extension to the pact before it was set to expire at the end of August 2023.? When the pact once again is about to expire, renewing the STA should be in the spirit of mutual benefit and shared commitment to the progress of humanity.

Sci-tech cooperation is a two-way street

According to Reuters, Burns told an audience at Brookings Institution that the agreement was the "bedrock" of U.S.-China cooperation, but controversy over the renewal of the STA has grown amid U.S. politicians.

As the first accord between the two countries signed in 1979, after the official establishment of diplomatic ties, proponents of renewing the deal argue that without it the U.S. would lose valuable insight into China's technological advances, while some Republicans in the U.S. Congress have the opposite view.

In October, The Economist published an article titled America and China should keep doing research together. The article pointed out the Republicans are wrong to want to scrap the STA, saying that quitting or watering down the STA would be a mistake.

There are few, if any, examples of academic collaboration harming America's interests. It would be a mistake to think that the gains from collaboration are a one-way street. China's scholars match and even outdo America's in some fields, such as batteries, telecommunications and nanoscience.

At a time of geopolitical tensions, the STA carries important symbolism. Scrapping it without good reason would feed the idea that America views all Chinese researchers with suspicion. If that deterred more talented Chinese from working in America, opportunities for fruitful cross-fertilization would go up in smoke, as American science benefits from its ability to attract the world's brightest minds. That would be impeded if it created the impression that it is a closed shop, The Economist described.

Keeping sci-tech channels open

An opinion and analysis article titled Broken U.S.-China Science Cooperation Needs Repair, Not Persecution published in Scientific American on October 10.

The article mentioned that when Stanford University physicists Steve Kivelson and Peter Michelson received word that the STA might not be renewed just a week before its expiration in late August, they spent the weekend composing a strongly worded letter of objection to the Biden administration.

They argued that the agreement, renewed approximately every five years, should not lapse. Instead every effort should be made to nurture open and transparent scientific cooperation.

American science writer KC Cole, said that, "Science plays an enormous unseen role in keeping international avenues of contact open, even when political doors slam shut. We need to keep those channels open with China."

"As someone who has been observing international scientific collaboration for many decades, and seen previous iterations of these kinds of crackdowns, I've come to conclude that U.S. policymakers don't understand what science is actually for," she said.

Of course, the primary business of science is to discover how the universe and everything in it work. But beyond advancing knowledge, science plays an enormous, often unseen role in keeping avenues of contact open even when political borders shut.

Like the arts, science is an essential part of our common humanity. Scientists share a common language and have ways of connecting that elude politicians; sometimes they provide the only glue that holds a fracturing world together. They allow enemies as well as allies to keep tabs on each other, added Cole.

According to Science Business, the agreement itself is a relatively brief document, but that doesn't mean it isn't important, said Deborah Seligsohn, a political scientist at Villanova University and former U.S. science counsellor to China. "These agreements are much more important with China than with other countries," she said.

Meanwhile, Jenny Lee, professor of higher education at the University of Arizona, said the U.S.-China science and technology agreement is a large gesture of goodwill between the two countries to work together on scientific advancement in ways that benefit both countries.